Reflections on CB9, Part 4: Opinions

[community-board Hello! This is Part 4 of my blog series reflecting on my time on Community Board 9. If you stumbled upon this post, I recommend checking out Part 1 for context first.

The previous entries in this series have aimed to be useful to all readers with some familiarity with community boards, regardless of their beliefs about local government and public policy. This final part, however, takes a different turn: I’ll share my personal thoughts and ideas about MCB9’s path forward, covering both housing policy and the board’s internal functioning.

I recognize that, as a one-term board member about to move cross-country, some readers might find it audacious to offer a long list of opinions about MCB9’s future priorities. Still, I offer these thoughts, hoping they spark conversation and curiosity among those who remain on the board.

While I cannot offer these reflections as a lifelong resident, I speak as someone who made West Harlem home for six years and cares deeply about its future. I also speak as someone whose generation faces a fundamentally different set of challenges, especially related to housing affordability.

Contents

On governance

Here are a few suggestions for strengthening MCB9 as an institution and improving its meeting flow. These relatively small-scale suggestions could make MCB9 more accessible and accountable.

- Make resolutions publicly available: CB9 does not consistently post its resolutions online. This makes it very difficult for new members and the public to understand past actions and ensure accountability. Other boards do this (see e.g., CB7’s airtable with links to all resolutions); MCB9 should follow suit.

- Guarantee time for debate: Our general board meetings are long, and the substantive business of voting on resolutions is often packed into the last few minutes of the meeting, with The Forum’s staff flickering the lights as a polite signal to conclude. Debate on key issues is frequently cut short, and CB9 members often cast votes without necessarily understanding what they’re voting for. I recommend considering a simple rule: every potentially controversial action item should be allocated at least ten minutes for debate and question, and the action items should be resolved early in the meeting. Our essential business should not be short-changed.

- Run more concise meetings: Multi-hour meetings make MCB9 less accessible to time-constrained community members, especially working New Yorkers with families. But where can we find spare time? Timing the lengthy reports of elected officials’ representatives would be a good start, and especially if they are encouraged to submit written updates. More careful time management for presentations and Q&A sessions could create more space for board deliberations and shorten meetings.

- Consider other venues: While The Forum is adequate for some purposes, its acoustics are atrocious. Virtual attendees are often either extremely loud or indecipherable, and loud conversations regularly interrupt us from across the room. Meetings held at City College, in contrast, offered a far better audience experience.

This isn’t to say that CB9 should become rigid and lose its spirited nature. I once had the displeasure of watching a CB5 meeting that was overwhelmingly legalistic and hostile. (At one point they voted on a third-order motion: “I vote yes on Motion C, which, if it passes, will dismiss Motion B. Motion B, if it passes, would in turn dismiss Motion A.” This took around 30 minutes to resolve.) I’d choose CB9’s familial culture any day.

However, CB9’s flexibility and free-wheeling nature has trade-offs. Multiple community members and board members have told me that they feel uncomfortable speaking up in unstructured meetings. A firmer adherence to Robert’s Rules at times may help make discussions more inclusive and productive.

On housing and land use

I joined CB9 to get involved with housing. I ultimately managed to be appointed to the Housing, Land Use, and Zoning (HLUZ) Committee, and I came to greatly appreciate the kindness, knowledge, and courage displayed by those committee members, especially Chairs Liz Waytkus and Signe Mortensen, and the former CB9 Chair, Barry Weinberg.

They strived to build on a housing vision crafted by the late April Tyler (whom I never had the privilege of meeting), which prioritized protecting affordable housing and ensuring that new development fit the cultural, economic, and historic fabric of the district. HLUZ leaders insisted MCB9 was not a “board of no,” upholding this commitment by supporting the new affordable construction under City of Yes and by explicitly advocating for zoning changes that would increase the number of affordable and supportive homes.

While I disagreed with my fellow committee members on a few projects–most notably the 135th St “Amtrak cantilever” ULURP–I mostly found myself in agreement with the Committee’s housing perspectives. I was thoroughly inspired by the dedication and resourcefulness my fellow committee members demonstrated when members of the public sought assistance with wrongful evictions, building fires, and questions about local law. I’m proud to have served on that Committee.

The next few sections present my thoughts on the current state of the housing affordability crisis in MCB9 and beyond. I’ll share a few perspectives on how I believe that MCB9 can fulfill its vision for housing and make a dent in its affordable housing crisis. These are organized around a few questions:

- Beyond CB9, how severe is the housing crisis, and what do solutions look like?

- What proactive steps can CB9 take to lessen the affordability crisis?

- Which sites are most promising for housing in CB9?

- Can CB9 support more homeless shelters and supportive housing?

I’ll close with reflections on the inherent challenges of treating housing as a local issue.

The case for more housing

Housing affordability is not just another issue. The public widely recognizes its urgency. A recent Siena poll vividly illustrated this:

- 94% regard affordability in NYC as a very or somewhat serious problem. 72% of respondents believe it is “very serious.”

- 88% of New Yorkers believe the availability of affordable housing is a very or somewhat serious problem. (68% said “very serious.”)

- 78% want the next mayor to prioritize increasing the supply of affordable housing.

- 59% identify it as the single most important initiative for the next mayor.

CB9 formally recognizes the importance of the issue as well. Our district Statement of Needs discusses the importance of housing affordability and calls attention to concerns about rising rents, tenant evictions, and building violations.

The affordable housing crisis also represents a profound generational shift. The social contract of my parent’s generation was built on housing that middle-class and working-class people could afford. My mom bought a house in coastal California in the 1990s on a public school teacher’s salary

That pathway is no longer available. An entry-level NYC teacher would need to spend over 60% of their starting salary to afford the median apartment in the city. Unaffordable housing has forced many of my peers to make painful choices: continuing to live in their parents’ house (and putting off key milestones), or being priced out of their hometowns. Friends and family members have postponed marriage and parenthood and been at risk of homelessness due prohibitively high housing expenses.

Almost everyone agrees that there is a housing crisis, but many disagree on the right causes and solutions.

There are many lenses through which the crisis can be examined. For this post, I’ll focus primarily on the housing supply lens. This isn’t to diminish major issues in affordable housing, including the protection of public housing and affordable co-ops, the development of social housing, and the preservation of a Right to Shelter. I believe CB9 members already have sophisticated understandings of these, and the HLUZ committee’s vision addresses them well. Rather, I concentrate on supply because I believe this is an area where we can–and should–push further.

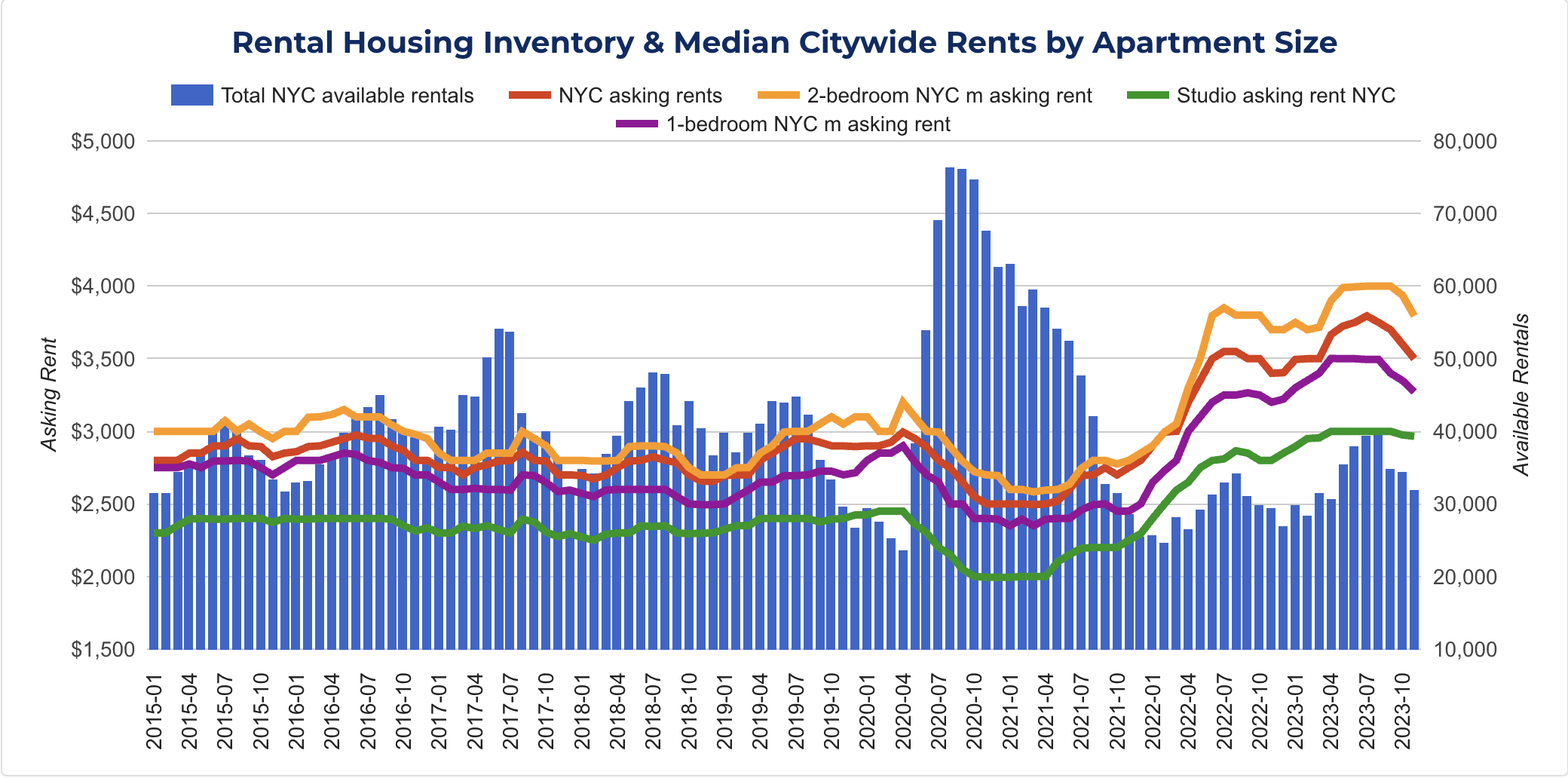

Recent reports from the NYC Comptroller highlight the severity of the housing affordability crisis, juxtaposing sky-high rents with low rental vacancies. As of 2023, median NYC rents had risen to an all-time high of $3500 per month, while vacancy rates had reached an all-time low. The plot below, which overlays median rents and available rental supply between 2015 and 2023, highlights a few facts:

- During the pandemic–while some New Yorkers fled the city–inventory skyrocketed and rents plummeted. (Remember those great pandemic deals?)

- In 2021 and 2022, supply dropped again as residents returned, and rents quickly rebounded.

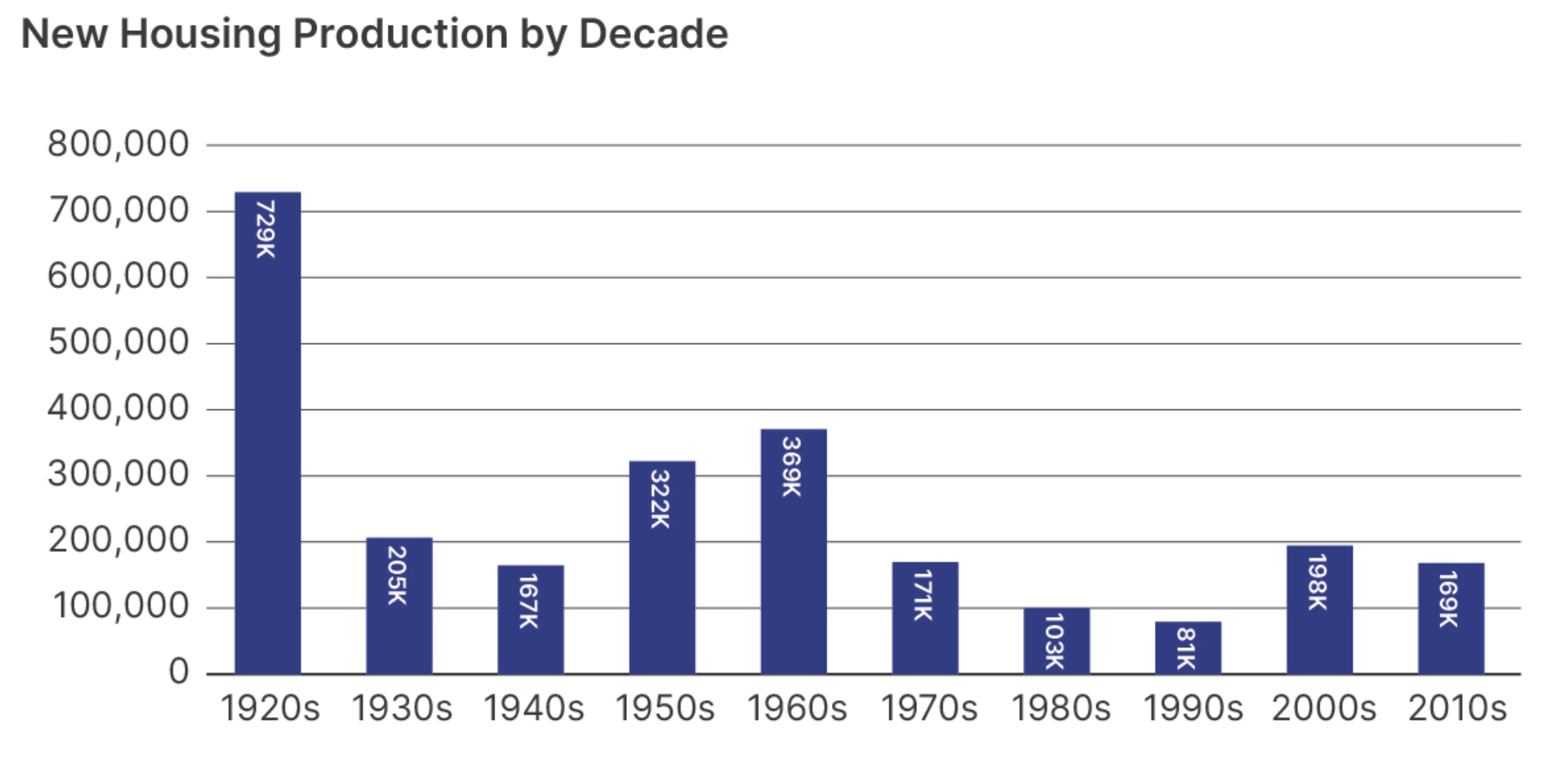

An inverse relationship between supply and rents is clear. When few NYC apartments are vacant, tenants outbid one another for the remaining units, driving prices up. Conversely, increasing housing supply decreases rents. Looking back on the last 100 years of NYC housing production, it’s readily apparent that NYC vacancy rates have plummeted as a result of decades of underbuilding.

Source: City of Yes

Source: City of Yes

The logic is clear: building housing of all kinds–income-restricted affordable housing, social housing, supportive housing, homeless shelters, and, yes, market-rate housing–is critical to raising the vacancy rate and reducing the burden of high rents. This isn’t just theoretical. Other cities have seen successes in reducing the burden of housing costs by building more housing. It worked in Austin. It worked in Minneapolis. And it worked nearby in New Rochelle.

Beyond affordability, building dense housing offers several other crucial benefits:

-

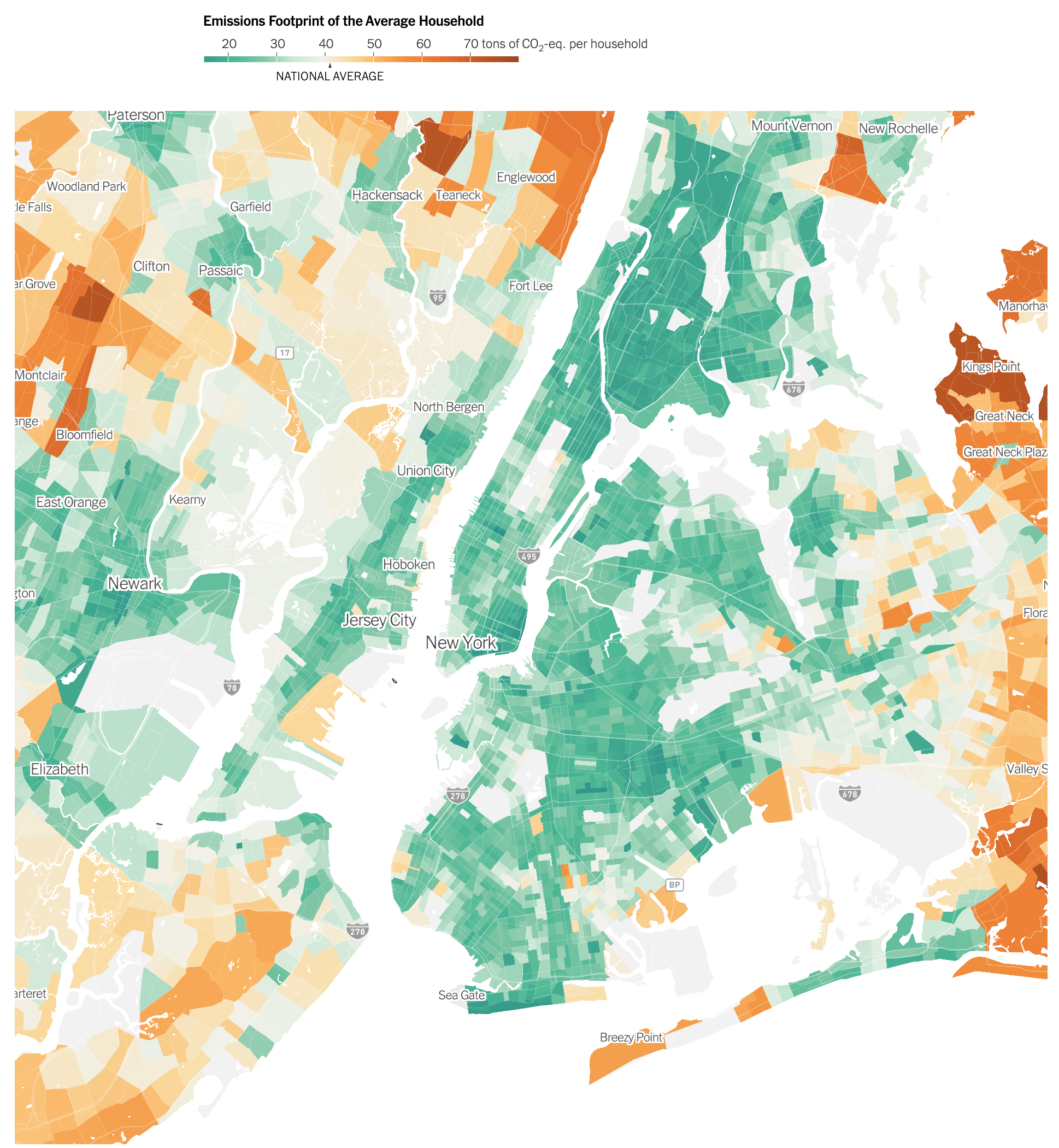

It’s a huge climate win. This New York Times map is one of my favorites. It illustrates the average household emissions by area, with lower emissions in green and higher in orange. Manhattanites’ average emissions are well under half those of residents in the New Jersey or Long Island suburbs. The accessibility of mass transit and the energy efficiency of multi-family homes are climate game-changers. MCB9 is one of the most environmentally-friendly neighborhoods in the country, and we should celebrate that.

Source: New York Times

Source: New York Times

Building dense housing extends those climate benefits to others. On the other hand, restricting the number of homes redirects potential neighbors to car-dependent suburbs with horrific carbon footprints. \ -

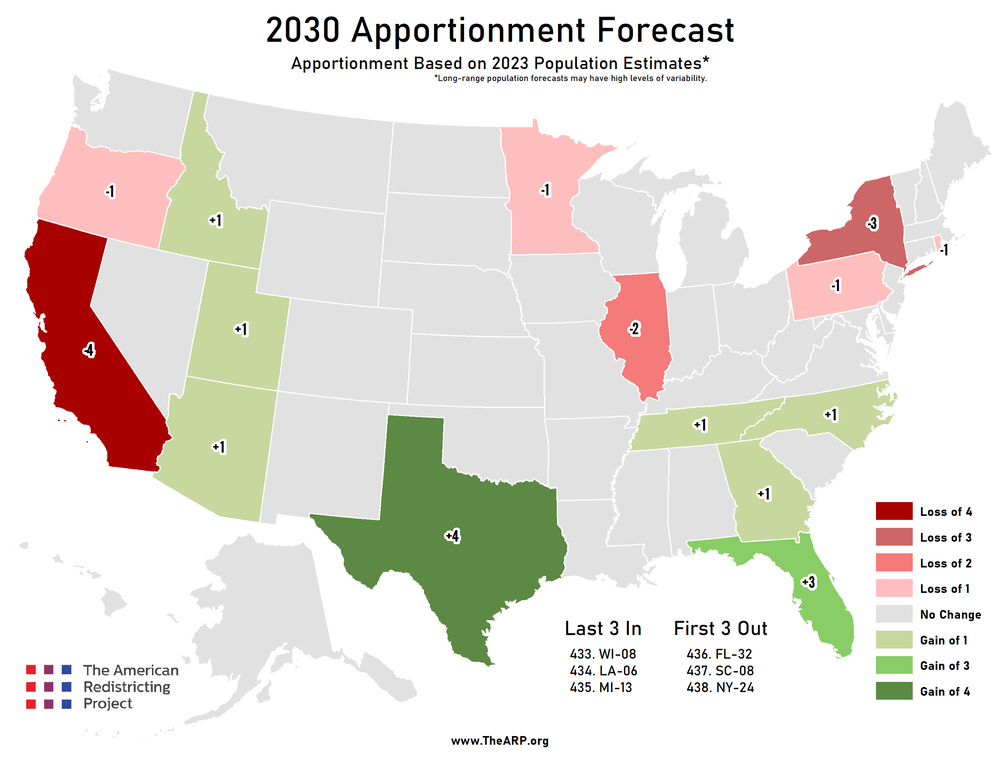

It’s electorally vital. New York stands to lose three representatives in 2030. Losing representatives means diminished political influence and greater difficulty electing national leaders who share our values. States poised to gain seats–Texas and Florida in particular–have massively grown their population through abundant housing.

Source: American Redistricting Project\

Source: American Redistricting Project\

Housing affordability is personal, and its connection to insufficient supply is well-documented. Let’s now pivot from the big-picture perspective to more local matters.

A proactive approach to housing affordability in CB9

The primary way to enable the creation of new homes is to change zoning policy to permit more widespread density.

The city-wide approval of the City of Yes for Housing Opportunity zoning text amendment was a good first step, and I’m proud of our resolution supporting it, which I helped author. Its most relevant provisions for MCB9–the removal of parking mandates, and the Universal Affordability Preference (UAP) that permits additional affordable homes–are promising. The latter provision is already being utilized in CB9. City of Yes’s provisions on Transit-Oriented Development (TOD), Town-Center Zoning, and Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs) will help boost production in less dense neighborhoods and ensure that all neighborhoods in NYC have a role to play.

But our board can and should do more. Despite our board’s pro-housing stances, MCB9 has one of the lowest production rates of new homes citywide, ranking 40th out of 59 community districts for housing completion between 2010 and 2023.

Source: Where is housing being added in New York City? (DCP)

Source: Where is housing being added in New York City? (DCP)

MCB9’s low production rate is not simply a function of Manhattan’s density. We produce fewer units than all but three other Manhattan community districts.

Source: Where is housing being added in New York City? (DCP)

Source: Where is housing being added in New York City? (DCP)

The primary tool for building more permanently affordable, income-restricted homes is the De Blasio-era Mandatory Inclusionary Housing (MIH) program. MIH requires a percentage of new units in upzoned areas to meet fixed affordability standards. Because very little of MCB9 has been upzoned since MIH’s inception, few developments MCB9 in MCB9 have been subject to these mandatory standards. (See this map.)

As a result, CB9 hasn’t built many new affordable homes either. Only 24 “very-low income units” were produced in CB9 between 2010 and 2023, compared to a citywide average of 198 units per community board (Source: OpenData). By contrast, Brooklyn CB5, built 1,752 very-low income units.

Finding a way to build more deeply affordable units is critical to easing the rental burden on our community members. I highlight this particular affordability band due to its deep relevance to our community: a very-low income unit is priced to be affordable for a family of three with a combined income of $58K, strikingly close to CB9’s estimated median household income of $57K.

The most promising way forward to produce affordable units for CB9 community members is to proactively pursue rezonings in sparsely-populated parts of the district. Those areas are few and far between, but there are a few options that can help MCB9 increase its number of affordable homes and contribute to citywide downward pressure on rents.

Morningside Heights Rezoning

The astute reader will note that this goal is already being pursued through the ongoing Morningside Heights Rezoning, spearheaded by the Morningside Heights Community Coalition (MHCC). If successful, the rezoning would permit dense construction near the 110th and 125th St stations for the 1 train, with MIH requirements.

Source: Morningside Heights Planning Study

Source: Morningside Heights Planning Study

The plan is a great start, and I admire the advocacy of the MHCC, particularly their efforts to build an elevator at the 125th St station.

The plan, however, could go further to enable even more affordable homes. Morningside Heights is an affluent and transit-accessible neighborhood. If more Columbia affiliates live in Morningside Heights, then the upward pressure on rents in the neighboring Harlem can be reduced. For specific changes, I would encourage upzoning lots near the 125th St station to R10A (rather than R9A) and increasing allowable density on the Broadway and Amsterdam corridors.

Other sites in CB9

CB9 is a dense residential district, which makes it challenging to pursue zoning changes without creating the risk of displacement for long-term residents. Consequently, I’ll focus on a few sites with limited current residential use. These are certainly not the only suitable locations for zoning changes; rather, I view them as potential starting points for a longer conversation about proactive visioning for housing across the district.

128th - 130th St, between Amsterdam and Convent: The retired bus depot between 128th and 129th Streets was identified in Mark Levine’s “Housing Manhattanites” document as a potential site for over 400 affordable homes. Just north of that site are the future sites of affordable and supportive housing at 478 W 130th St and 487 W 129th St, respectively; the HLUZ committee had previously suggested a targeted upzoning on those sites to increase the number of affordable units. MCB9 could take the lead on creating a broader housing vision for this area, which offers excellent transit connectivity and proximity to the new Manhattanville Factory District biotech offices.

12th Avenue Corridor: The area west of the future Columbia Manhattanville campus is well-connected to the West Harlem Piers Park and the Hudson River Greenway. Existing zoning is primarily manufacturing. In the past, MCB9 has led visioning sessions on activating the space for community members. The right vision for the neighborhood–shaped by CB9–could enable new homes with minimal risk of displacement.

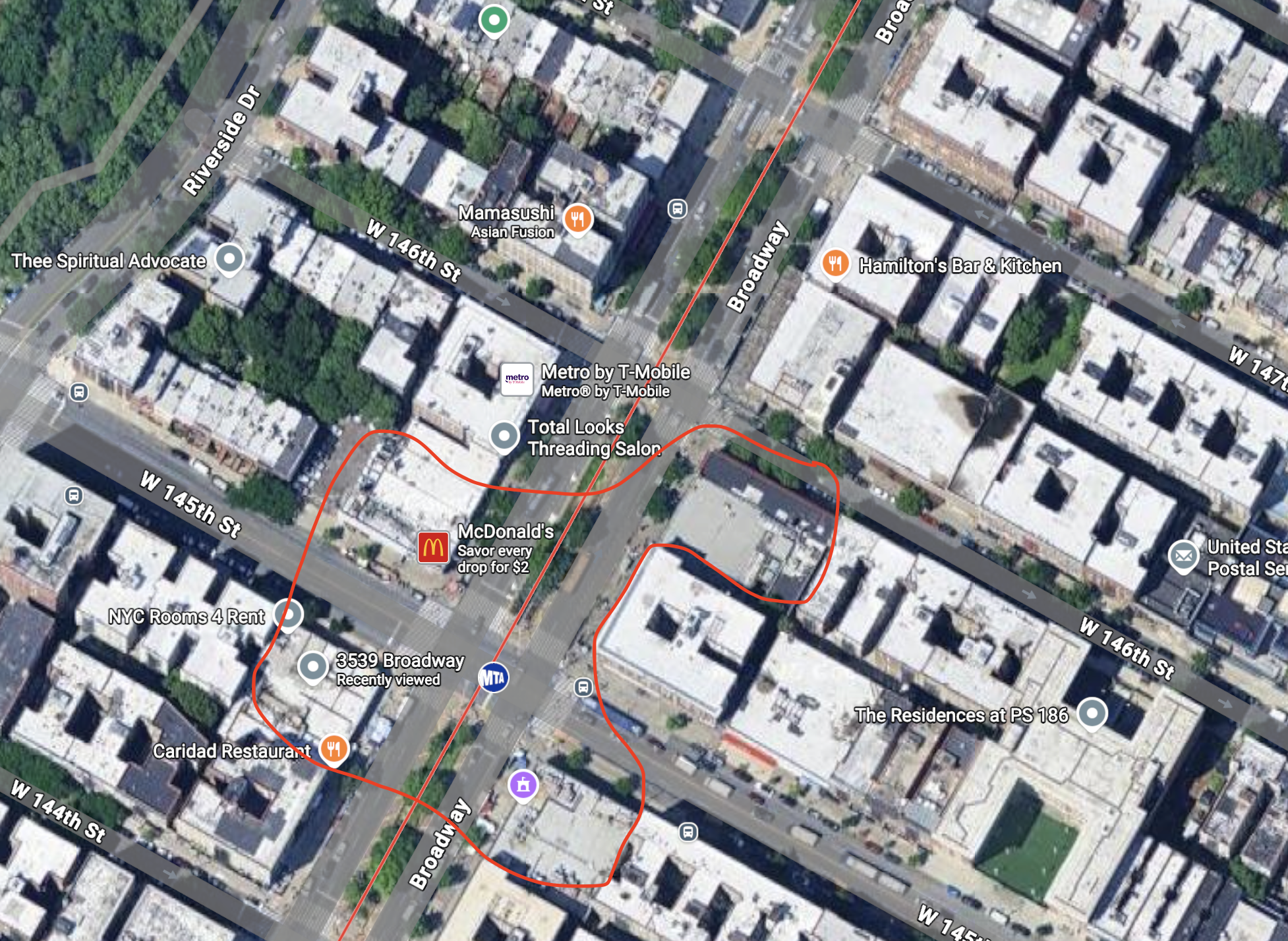

145th St 1 Station: 3 out of four buildings at the corner of this subway station have single-story commercial uses. Replacing them with residential infill would provide fantastic transit connections and avoid displacement. Furthermore, the 145th St station is inaccessible and lacks elevators; CB9 could explore using the Zoning for Accessibility program to incentivize new buildings to provide elevators to the underground station.

Shelters & Supportive Housing: Ask for the numbers

At MCB9 meetings, I often hear the narrative that our district is uniquely overburdened by homeless shelters and supportive housing, prompting calls for a moratorium on such units. I deeply sympathize with the fear and frustration underlying these feelings. It’s true that residents near 145th St and Convent Ave in MCB9 bear a high concentration of these facilities, and I support MCB9 proactively working to ensure a more equitable distribution of services across all district neighborhoods.

However, I believe a blanket moratorium on supportive units and shelters would be short-sighted and detrimental to citywide efforts to help those who have experienced homelessness, addiction, or domestic violence. While comprehensive counts of shelter and supportive units and occupancy are challenging to access given their private nature, the data I’ve found suggests that MCB9 as a whole is not overburdened compared to nearby districts. Maps from The City indicate that CB9 has fewer shelter beds than neighboring districts (CB7, CB10, CB11, and CB12), and City Limits reports the number of individuals sheltered in CB9 closely matches the number of homeless individuals who originate from our district.

These are difficult and delicate questions, and I agree that these numbers don’t negate the possibility that certain supportive housing types might be disproportionately present. But New York City cannot address systemic homelessness and mental illness without expanding its shelter and supportive housing capacity. This cannot happen if individual districts claim they’ve “done enough.” An inability to provide shelter jeopardizes NYC’s ability to maintain its Right to Shelter, a vital protection that Mayor Eric Adams suspended in 2023.

Tension: Hyper-local vs regional framing

I recall a general board meeting where Public Advocate Jumaane Williams attended virtually. A board member asked him what could be done to ensure that homeless New Yorkers were sheltered, safe, and treated with dignity. Williams responded by asking board members who thought that new shelters needed to be built for homeless New Yorkers; nearly every hand went up. He then asked who would be willing to have a shelter built next door to their home; almost all hands fell.

MCB9 housing resolutions often argue that the burden of building new homes should primarily fall on the outer boroughs, given their lower density and greater construction potential. It’s a reasonable claim, but outer borough community boards often argue the opposite: Why should they, having not chosen an urban lifestyle, be obligated to change on Manhattan’s behalf? Regardless of which side is more “correct,” a system that prioritizes local deference will fail to build a sufficient number of homes if every neighborhood defers responsibility to the other.

These two examples capture a core tension of local politics. No single community board can solve a regional crisis through its own local policy. This creates a tragedy-of-the-commons, where every locality has an incentive to say “no.” There is a shared understanding that someone needs to build the homes and shelters, but a disagreement on who that is.

Of course, the risks of ignoring community voices are self-evident. Community Boards were originally envisioned as a counterweight to power-hungry Robert Moses-like officials. Hyper-local oversight is important to protect residents from some of the horrific destruction of mid-twentieth century urban planning.

Some issues–like housing and homelessness–may ultimately require city-level and state-level solutions, particularly if local deference renders regional issues unsolvable. This trajectory can be seen in California, where decades of local failure to produce housing has caused the state to assign zoning quotas to localities via the Housing Element system.

Efforts like City of Yes can be seen similarly, and I was heartened by our support for it. It signaled MCB9’s appreciation for the scale of the problem and its acknowledgement of our role to play.

Farewell

I hope these thoughts–whether agreed with or not–spark conversations among those who remain on MCB9 about how to build a better city and a better board.

With this screed complete, I shall take my leave. I welcome thoughts and comments; please email me at claytonhsanford@gmail.com.

I am now a former board member and will soon be a former community member. I will deeply miss CB9–Morningside Heights, where I lived for five years, and Hamilton Heights, where I lived for one. I will miss the late nights on the HLUZ Committee, the cultural richness of the West Harlem LGBTQ community (for which I planned events), and the opportunity to witness the dedication that binds us together. I witnessed it at meetings, on walks, and at the memorial service for the late Carolyn Thompson, who contributed so much over decades of service and made new board members feel like a part of something special. I am grateful to have been a neighbor in West Harlem during this chapter of my life.

I treasure the connections and the memories I’ve formed, and I wish you all the best.