Reflections on CB9, Part 1: Introduction

[community-board Welcome to my blog series reflecting on my time as a board member of Manhattan Community Board 9.

In case you don’t know me, hello! My name is Clayton. I’ve lived in West Harlem for six years, the first five of which I spent as a PhD student at Columbia University, researching computer science and math (see my personal website) while living in student housing.

In 2023, I applied to my local community board and served until my term expired last month. This series of blog posts distills the lessons learned during my two-year term for anyone interested. Here in Part 1, I’ll provide some background before outlining the rest of the series.

Contents

What are community boards?

For the uninitiated—like those arriving from my personal website or other posts—a little context is helpful.

Community boards (CBs), a neighborhood-level branch of New York City government, incorporate grassroots feedback into city decisions on issues such as housing, transportation, and parks. NYC is divided into 59 community districts, each with a board of 50 all-volunteer members appointed to renewable two-year terms. The borough president or a local city council member appoints board members after they submit an application and participate in a group interview. Many NYC politicians launched their careers as CB members, and community leaders often serve for decades.

Community boards hold a few formal responsibilities, including votes on zoning code changes, budgetary requests for local projects, and approvals of liquor licenses. Most decisions are non-binding and can be overridden by elected officials. However, city officials frequently rely on CB resolutions to gauge public opinion and to justify their ultimate decisions. Proposals for major policy changes–like the City of Yes rezoning program and the trash containerization pilot–are presented, debated, revised, and ultimately voted on in CB meetings. CBs also provide hyper-local, often overlooked, feedback, such as requesting porta-potties at the West Harlem Piers Park after a nearby supermarket’s closure left parkgoers without restrooms.

What is MCB9?

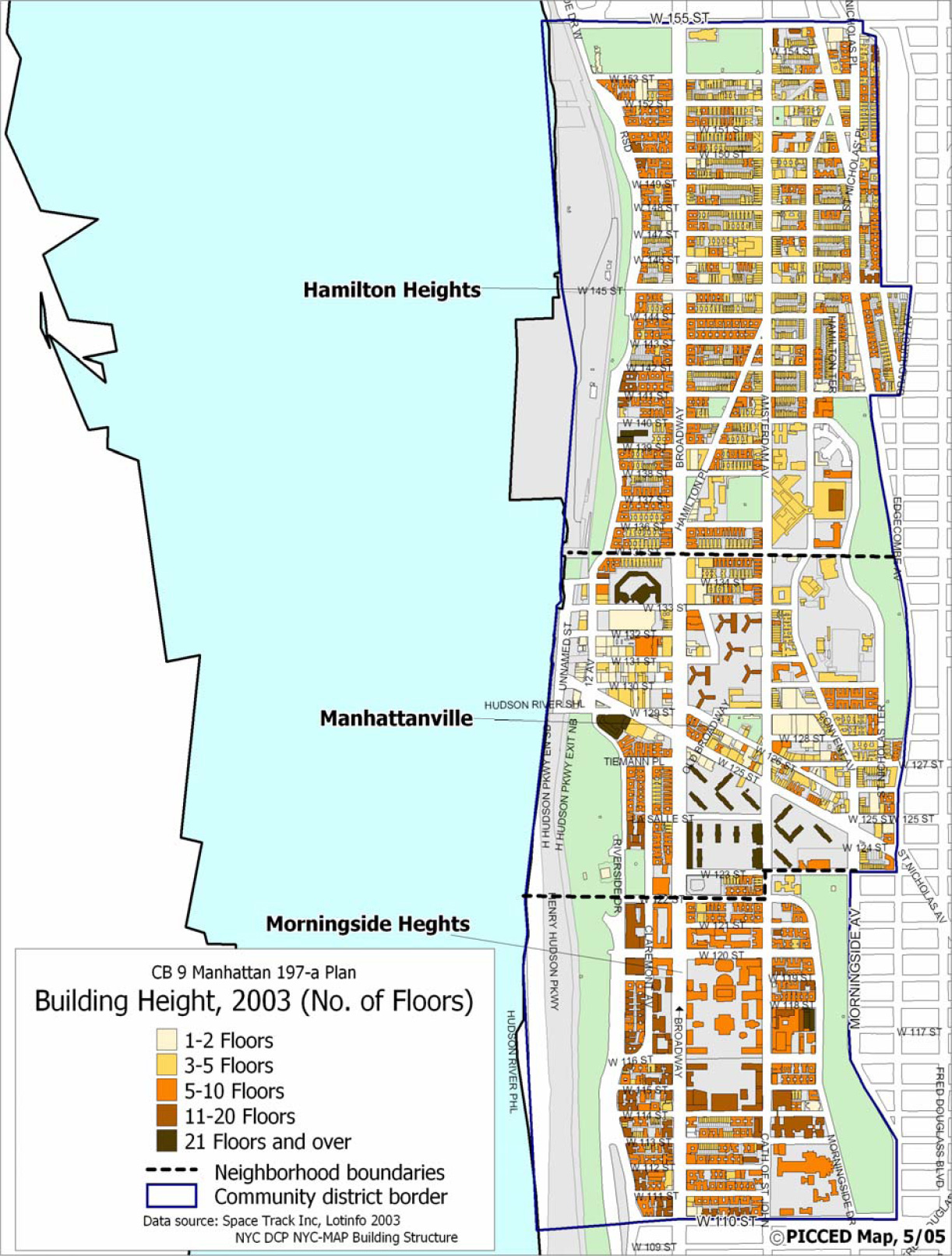

Manhattan Community Board 9 (MCB9) represents West Harlem, encompassing the neighborhoods of Morningside Heights, Manhattanville, Hamilton Heights, and Sugar Hill. Its boundaries are 110th St, 155th St, the Hudson River, and a chain of “long skinny parks” (Morningside, St Nicholas, Jackie Robinson). MCB9 hosts multiple academic institutions: Columbia, Barnard, City College, Union Theological Seminary, and Jewish Theological Seminary. The city maintains a district profile that offers helpful information about demographics, housing, and amenities. (Part 2 will discuss data and resources in much greater depth.)

MCB9’s fifty members are organized into committees; each typically serves on two committees and attends three meetings per month (two committee meetings and one general board meeting). The community board elects a chair who runs the general board meetings, makes committee appointments, and represents the board at various other meetings. All meetings are hybrid and open to the public and can be found on this calendar. The state’s Open Meetings Law requires public access to meeting minutes and recordings.

The board conducts its formal business by issuing resolutions (“resos”) that pass a committee vote before full board approval. These resolutions may be reactive (for example, responding to requests for rezoning or licenses) or proactive (advocating for particular legislation or requesting funding for certain programs). Some resolutions can be found online. Below are a few representative resos from CB9.

- This resolution from the Housing, Land Use, and Zoning (HLUZ) Committee endorses a state assembly bill to prohibit requiring tenants to pay their landlords’ broker fees. (A local version of this bill recently passed and is about to take effect.)

- Another reso from HLUZ opposes a proposed single-lot rezoning next to the Amtrak line.

- This reso approves and renews liquor licenses of several establishments. (This is a routine business handled by the Uniform Services and Transportation Committee.)

- This collection of resolutions from the Health and Environment Committee advocates against the removal of subway station benches and the cancellation of a diabetes research program by DOGE.

Most resolutions pass the full board with unanimous, or near-unanimous support. (The rezoning reso passed with only two members in opposition, including yours truly.) In addition to resolutions, a primary formal obligation of each community board is issuing an annual Statement of Needs that outlines funding requests and fiscal priorities for the district.

MCB9 also oversees the disbursement of funds from a community benefits agreement (CBA) with Columbia University. Columbia is currently constructing a new Manhattanville campus north of 125th St. As a condition of the city’s approval for this massive expansion, Columbia agreed with MCB9 and the NYC government to contribute $150M in community benefits to West Harlem over a 25-year period. These include $20M for affordable housing, $20M in in-kind benefits (free usage of Columbia facilities), and $76M for local organizations. MCB9 plays a substantial role in overseeing the final category, disbursed by the West Harlem Development Corporation (WHDC), which. MCB9 helps govern. The nonprofits WHDC funds are expected to report annually to the board’s relevant committees.

Beyond these formal roles, MCB9 acts as a community outreach organization, with priorities set largely by board members. Much meeting time is devoted to listening as community members share concerns and advocate for specific issues. CB members often advise the public on how to approach government agencies and elected officials for their needs. This is particularly common in HLUZ meetings, where community members often seek advice about eviction protections and affordable co-op resources. CB committees also hold outreach events, such as a small business forum by the Economic Development Committee and a film screening by the SGL-LGBTQ Taskforce.

If you’re interested in learning more, I recommend attending a few meetings to get a feel for them. They can be long and dry at times, and theatrical and chaotic at others. (The first meeting I attended featured a spirited battle over renewing the liquor license of the Baylander, a boat bar docked at the West Harlem Piers Park.) If you’re passionate about local issues–affordable housing, parks, trash containerization, public access to campuses–MCB9 meetings are a place to make your voice heard and listen to what others think.

My involvement with CB9

Like many twenty-something city-dwellers, I often fixate on two thorny policy questions:

- Why is housing so unaffordable and how can we reduce that burden?

- Why is it so difficult for NYC (of all places) to invest in public transit?

Before joining, my preconceptions of how community boards approached these issues was fairly negative. Citywide, CBs skew older, whiter, and wealthier than the districts they represent. As a result, their decisions often center car-owners and lack urgency regarding housing affordability. Neighborhood-level organizations frequently provide the loudest opposition to new housing of all kinds and transit infrastructure.

While many of these characteristics do not apply to MCB9, our district still has a long way to go on key housing and transit issues. In particular, CB9 lags behind its peers in new homes and bike lanes. I was interested in joining the board to provide a voice for those issues.

I also wanted to get involved to find a way to escape the Columbia bubble. As a PhD student in my mid-20s in NYC, I easily found myself interacting only with other students, faculty members, and young professionals. Community boards generally–and MCB9 particularly–offer members a chance to join a multi-generational community of civically-minded individuals, rooted in a shared sense of place.

I first attended a meeting in February 2020 to evaluate whether the board was a good fit. I was taken aback by its free-wheeling nature (particularly regarding the Baylander debate) but impressed by the depth of local knowledge attendees shared. I was interested in learning more and getting involved… but we all know what came next. With the pandemic in full force and meetings entirely virtual, I set aside my interest for a few years.

That interest resurfaced in 2023. I applied in the spring and was appointed. While on the board, I served on the Economic Development Committee; the Housing, Land Use, and Zoning Committee; and the SGL-LGBTQ Task Force. (SGL stands for “same-gender-loving,” and is most commonly used by members of the Black community.)

Former Assemblymember Denny O’Donnell once said at a general board meeting that attending CB9 feels like going to church. While I’m not particularly religious, I find that sentiment rings true. CB9 members are comfortable disagreeing with one another, but meetings start and end with kind greetings and open affection. Board members are generous with their time, expertise, and stories, and are generally interested in other perspectives. While this isn’t true for all community boards (as some friends can attest), it was certainly my experience.

These blog posts

I hope these posts serve as a resource for current and future MCB9 members, sharing what I’ve learned from my time on the board. (Some of this guide will be relevant only to MCB9, while other parts may generalize citywide.) Here’s how it’s structured.

-

Part 2: Resources. This includes a list of documents, datasets, and tools that I’ve found useful for my work as a CB member and for better understanding the needs and characteristics of the district. The board possesses an overwhelming amount of institutional know-how, especially on land use, and I hope this series makes that information more accessible for new members.

-

Part 3: Lessons. I learned a lot on the board and made many mistakes. This is a brief recap of some of those lessons, distilled down mostly for new board members.

-

Part 4: Opinions. A fifty-person board has fifty different sets of opinions. This post includes some of mine, with a focus on board governance and housing policy.

While I’ve tried in Part 1 to explain as much as possible for general audiences, I’ll mostly assume in the subsequent posts that readers have some kind of involvement with MCB9; otherwise, there would be too much to cover.

Many of my peers on the board are far more knowledgeable—and new members should absolutely seek their counsel. However, I believe there is value in documenting every perspective. Institutional memory is important, and I’d like to have this as a record, hoping it provides value to those who remain on the board. I’m grateful for how much I learned during my time on MCB9––mostly from more experienced board members––and I hope that knowledge is more accessible as a result of these blog posts. Feedback on this series is greatly appreciated; email at clayton.h.sanford@gmail.com.

Being on CB9 has been a great privilege, and I am grateful for the people I met. I’d like to extend special thanks to dedicated and brilliant board leaders like Victor Edwards, Barry Weinberg, Liz Waytkus, Signe Mortensen, and John-Martin Green for their leadership and guidance; to Chris Johnson for the long walks and conversations; and to my other colleagues for their kindness, curiosity, commitment, and effort. I have treasured this experience and will miss it.